The FDA is required to produce a yearly report that addresses the number of petitions filed during the previous year, the number of those petitions that were designated as 505(q) petitions, and the number of the 505(q) petitions that delayed whether a 505(b)(2) application, ANDA or biosimilar approval.

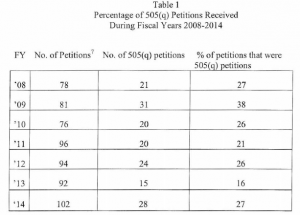

The FDA report (here) indicates that, during the previous year period (2014), only one 505(q) petition actually delayed the approval of one application (a 505(b)(2) NDA). There were 102 petitions submitted to FDA in FY 2014; of those, 28 were characterized as 505(q) petitions. So what’s the problem if only one petition delayed the approval of any application? Well, FDA is concerned about the resources that are devoted to responding to the petitions that could have been better spent reviewing applications The following tables come from the FDA report and describe the numbers of petitions, outcomes of petitions and delays caused by the petitions (if any).

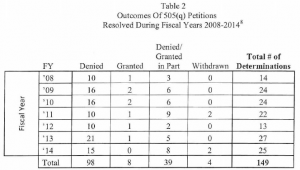

Many petitions are denied outright (98 over the 7-year period), only 8 were fully granted, and 39 were granted in part and denied in part. Typically, of those petitions that have been granted or granted in part and denied in part, many of the grants represent requests by petitioners to do what the FDA would have required anyway. For example, the inclusion of a requirement for a fed study where the standard practice would be for the FDA to require a fed study for that type of product. There are some petitions where FDA goes beyond requiring normal requirements, as may be the case when a petitioner successfully argues for a safety or efficacy requirement. For example, where the inclusion of a partial AUC may be required to better define the pharmacokinetic curve for establishing bioequivalence, when the innovator has successfully demonstrated a clinically significant difference in pharmacodynamics response should the actual pK curve not match that of the innovator.

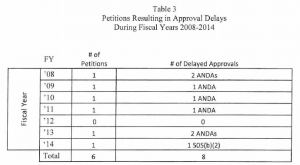

Over the 7 years FDA has been tracking these types of petitions, a 505(q) petition has delayed the approval of 7 ANDAs and only one 505(b)(2) application. This may seem fairly small when considering the number of ANDA and 505(b)(2) applications that have been submitted to the Agency over this time period; however, many petitioners submit serial petitions, e.g., multiple petitions over time that address the same basic issue with new twists that result in a substantial FDA effort, which compounds the impact on the use of scare resources. In addition, FDA notes that FDASIA has increased the strain on Agency resources by shortening the statutory response time from 180 says to 150 days.

So, all in all, while the numbers of 505(q) petition does not seem that large, FDA is still concerned that the 505(q) process is not discouraging the submission of these petitions that may not all have scientific merit, which it was designed to do. And FDA remains worried about the resources required to respond to these complex petitions within the 150-day time frame required by the statute. Interestingly enough, although the statute does give the Agency authority to deny a 505(q) petition straight away if the Agency determines that the petition is solely designed to delay the approval of an ANDA, 505(b)(2) NDA, or a biosimilar application, the FDA has never (according to the report) utilized this provision of FDASIA.