Coauthored by Kurt Karst (of FDA Law Blog) and Bob Pollock

The “Petitioned ANDA”—It’s a route to ANDA approval that’s been around since even before the enactment of the 1984 Hatch-Waxman Amendments. For several years after the enactment of Hatch‑Waxman, the petitioned ANDA was a mainstay of the generic drug industry’s drug development paradigm. And although it remains a viable route for many generic drug applicants to obtain approval of a drug product without having to conduct expensive and time-consuming clinical studies, the popularity of the petitioned ANDA has waned in recent years. The continued success—and reinvigoration—of the petitioned ANDA depends in large part on the FDA’s ability to promptly review and act on ANDA suitability petitions within the statutory ninety-day period. But we’re getting a little ahead of ourselves…

In this blog post—posted simultaneously on the FDA Law blog and the Lachman Consultants blog—we hope to describe the benefits of the ANDA suitability petition process, look at why it is not working, and suggest some actions the FDA might consider to get the program back on track.

Codified at FDC Act § 505(j)(2)(C), the ANDA suitability petition is used to request the FDA’s permission to submit an ANDA that differs from a brand-name Reference Listed Drug (“RLD”) in strength, dosage form, route of administration, or for the substitution of one active ingredient of the same therapeutic class for another active ingredient in a combination drug (when, and only when, there is a known equipotent dose relationship between the two ingredients). Over the years, the FDA has received somewhere in the neighborhood of 1,500 ANDA suitability petitions.

The ANDA suitability petition provisions of the FDC Act are short and total slightly more than 150 words:

If a person wants to submit an abbreviated application for a new drug which has a different active ingredient or whose route of administration, dosage form, or strength differ from that of a listed drug, such person shall submit a petition to the Secretary seeking permission to file such an application. The Secretary shall approve or disapprove a petition submitted under this subparagraph within ninety days of the date the petition is submitted. The Secretary shall approve such a petition unless the Secretary finds—

(i) that investigations must be conducted to show the safety and effectiveness of the drug or of any of its active ingredients, the route of administration, the dosage form, or strength which differ from the listed drug; or

(ii) that any drug with a different active ingredient may not be adequately evaluated for approval as safe and effective on the basis of the information required to be submitted in an abbreviated application.

It’s the twenty-two emphasized words above that we focus on here because prompt FDA action on a suitability petition is critical to a vibrant suitability petition program. As one of the authors of this post pointed out in a law review article a few years ago, titled “Letting the Devil Ride: Thirty Years of ANDA Suitability Petitions under the Hatch-Waxman Amendments” (here), the FDA’s track record of timely ruling on suitability petitions has been less than stellar.

The Benefits of Suitability Petitions

As noted above, the changes permitted in a suitability petition allow for certain defined changes from that of the RLD if no new safety or efficacy data are necessary to support the proposed change. Most suitability petitions are approved for changes in strength and dosage form, rather than for changes in route of administration and active ingredient in a combination drug. (Today this may be largely due to the Pediatric Research Equity Act of 2003, which amended the FDC Act to add Section 505B to give the FDA the authority to require sponsors of applications submitted under FDC Act §505 for a new active ingredient, new indication, new dosage form, new dosing regimen, or new route of administration to conduct testing in pediatric populations. An ANDA requiring an approved suitability petition for a change in the RLD in an active ingredient, route of administration, or dosage form triggers PREA because it is a type of application submitted under FDC Act § 505. The statute requires that the FDA deny a suitability petition if “investigations must be conducted to show the safety and effectiveness of the drug or of any of its active ingredients, the route of administration, the dosage form, or strength which differ from the listed drug.” The requirement to conduct (or even a deferral from conducting) pediatric studies triggers the statutory requirement to deny a suitability petition. Thus, unless the FDA fully waives the PREA pediatric studies requirement, the Agency must deny a suitability petition that requests permission to submit an ANDA for a change in route of administration, dosage form, or active ingredient vis-à-vis the RLD.)

Changes proposed in a suitability petition may significantly improve patient compliance. For instance, if a drug is available in 25-mg and 50-mg tablet strengths and the labeling of the RLD states that that single doses of up to 150 mg may be required for certain patients, then a change to include a 100-mg scored or 150-mg tablet may help a patient take fewer dosage units to achieve the required dose. In other instances, approval of intermediate dosage strengths may help patients who otherwise have to break tablets at scoring marks to reach those doses. This may be even more important for the elderly, infirmed, or visually impaired patients. Other changes, such as from a tablet to a capsule (and vice versa), may help patients who have difficulty swallowing either tablets or capsules. In addition, approval of oral solutions could aid in the delivery of drugs to patients that have dysphagia or other maladies, or those patients who just cannot seem to swallow solid dosage forms.

The suitability petition process also permits drug companies to expand available generic products (thus creating greater competition while potentially addressing a current unmet need), while at the same time avoiding the use of the more resource-intensive (and expensive) 505(b)(2) NDA process for the same types of changes permitted under a suitability petition.

Why the Suitability Petition Process is Not Working at the FDA?

Input for reviewing suitability petitions and their proposed changes is required from various FDA components in the Center for Drug Evaluation and Research (“CDER”). While the number of CDER components that chimed in on suitability petitions was small at first, that number has grown significantly over the years, resulting in an unwieldly process.

At the time of the passage of the Hatch-Waxman Amendments, there was a small committee comprised of two people from the Office of Generic Drugs (“OGD”), Dr. Jim Bilstad and Dr. Bob Temple (the only two Office Directors at that time), and a member of the Office of Chief Counsel (“OCC”). Staff work with recommendations was prepared by the OGD and forwarded to the respective CDER Division Directors, who were responsible for the RLD, and decisions were made at monthly suitability petition committee meetings. If the CDER Division Directors did not object and the committee’s recommendation was to approve the petition, then the final decision rested with the committee. If the CDER Division Directors or if the committee recommendation was to deny the petition, then a draft denial letter was prepared and run through the OCC representative and an action letter was prepared.

Today there are too many cooks in the kitchen! There are many more CDER Office and Division Directors who need to have a “say” in a suitability petition decision. Moreover, the institutional knowledge regarding suitability petition precedent has, with a very few exceptions, been lost. This further slows down the process. And then there’s the post-PDUFA and GDUFA environment at the FDA where a significant amount of the CDER’s attention is directed towards meeting user fee goals. Despite the fact that the FDC Act directs the FDA to rule on a suitability petition within ninety days of submission, it’s not a user fee goal. As such, the FDA has essentially let the suitability petition process go adrift in favor of addressing “higher” user fee priorities.

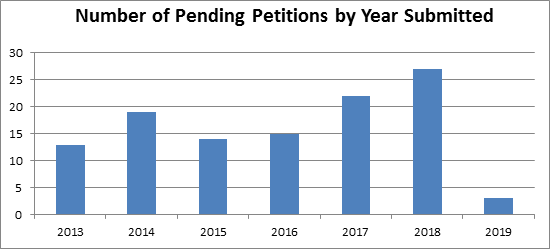

The Association for Accessible Medicine (“AAM”) estimates that hundreds of ANDA suitability petitions are currently pending at the FDA. Some of those petitions have been pending at the FDA for over eight years! According to data compiled from the FDA Law Blog Citizen Petition Tracker, the FDA received 135 ANDA suitability petitions between 2013 and 2019. Of those 135 petitions, an astounding 113 (or 84%) remain pending (see table below). Of the twenty-two petitions that have been resolved, two (1.5%) were denied, five (4%) were granted, and fifteen (11%) were withdrawn (with half of those petitions later resubmitted and still pending).

Delving deeper into the numbers, we see that two of the pending petitions are for drugs that are in shortage, and for which the brand-name RLD is not marketed: (1) sodium chloride, 23.4%, which is regularly used as a diluent for intravenous infusions; and (2) cysteine hydrochloride injection, 5%, which provides amino acid therapy to newborn infants. In each case, the changes requested are merely to the volume of product provided (i.e., strength) and raise no new safety or effectiveness questions. While these petitions remain pending, patients are without an option for these products. Twenty of the pending suitability petitions concern drugs that have no generic competition. And six of these are on the FDA’s List of Off-Patent, Off-Exclusivity Drugs without an Approved Generic. These drugs are for indications including type 2 diabetes, cancer, heart disease, and broad-spectrum antibiotic uses (here).

The FDA’s efforts to address the ANDA suitability petition backlog have thus far been unsuccessful. For example, in August 2013, the FDA published a Manual of Policies and Procedures (“MAPP”) establishing the policies and procedures for responding to suitability petitions and reiterating that “the Agency will approve or deny the petition no later than ninety days after the petition is submitted.” That MAPP—MAPP 5240.5, revised in August 2018 to remove any reference to the ninety-day period—has not resulted in any noticeable change in the speed with which the FDA responds to suitability petition (here). Heck, the FDA has not even updated the Agency’s ANDA Suitability Petition Tracking Reports since August 2015! (here)

Perhaps as a result of the FDA’s failure to timely address suitability petitions, Congress expressed its expectation that the FDA meet this ninety-day target in Section 805 of the 2017 Food and Drug Administration Reauthorization Act (“FDARA”). In addition to a “sense of Congress” provision stating that the FDA “shall meet the requirement under [FDC Act § 5050)(2)(C)] and [21 C.F.R. § 314.93(e)] of responding to suitability petitions within ninety days of submission,” Congress hoped to encourage the FDA to expedite responses to such petitions by requiring a report of the number of outstanding suitability petitions and a report of the number of suitability petitions that remained outstanding 180 days after submission. FDARA § 805. In addition, the GDUFA II Performance Goals Letter states that the “FDA aspires to respond to Suitability Petitions in a more timely and predictable manner.” GDUFA II Performance Goals Letter at 23. The FDA has thus far not complied with this congressional mandate and GDUFA II Performance Goal.

As a result of the current disfunction of the ANDA suitability petition process, firms have instead been using the 505(b)(2) NDA route as it covers the same type of changes permitted by an ANDA suitability petition. But the submission of a 505(b)(2) NDA not only means the payment of a hefty application user fee, but also annual program fees (in some cases).

How to Fix the ANDA Suitability Petition Process?

There are two paths that we believe the FDA could take to address the suitability petition backlog and to lay the groundwork for future success.

First, the FDA could contract out the staff work to develop a recommendation based on the statutory and regulatory requirements and past precedent that the Agency could use as a basis for its final decision-making process. This approach may raise some eyebrows as there could be hints of conflict of interest from private contractors relative to their potential affiliations.

Second—and perhaps the best approach—would be for the FDA to detail a select few individuals to spend a good portion of their day managing the suitability petition process with the goal of cleaning up the backlog of petitions and establishing a foundation upon which future petitions could be handled within the Agency. The use of those with historical perspective should be of greatest benefit for the FDA, and its wisdom could then also be transferred to others within the Agency. This “suitability petition hit squad” may be able to revive the vibrancy of the petition process while providing the FDA, patients, and industry with the service it deserves and a long-term solution for continuing the process going forward.

Absent the FDA being able to address the issue internally, Congress might have to step in and make some changes to the statute. For example, Congress might consider extending—perhaps as part of the next iteration of GDUFA––the ninety-day response deadline to reflect deadlines that are more familiar to and attainable by FDA, such as the 150-day, 180-day, or 270-day petition response deadlines imposed by Congress in recent years.

An attainable deadline will give greater certainty to the ANDA suitability petition process, will reassure the generic drug industry that it is a viable and practical route to ANDA approval, and may lead to a renewed interest in submitting ANDA suitability petitions.